Complexity in

Seventeenth

Century Southern Ontario Burial Practices

Mary Jackes, Department of Anthropology, University of Alberta

Edmonton, AB, Canada T6G 2H4

Published in Debating Complexity Proceedings of the 26th

Annual Chacmool Conference, University of Calgary, 1996.

back to index

Introduction

Complexity in burial practices implies social differentiation,

signalled

to an archaeologist by variations in funerary structures or grave goods

(e.g. Gualtieri and Jackes, 1993; Rothschild, 1979). To a skeletal

biologist

complexity may imply differentiation by age, sex, state of health,

family

relationships. If a mortuary practice allows us to distinguish

groupings

among skeletons on these bases, then the burial practices are complex,

even though grave goods or burial type may not be unequivocally

differentiated.

The next step in interpretation might be that a society with

differentiated

burial practices is more "complex" than a society with simple

undifferentiated

burials. On the evidence to be presented, this step is unwarranted. Two

very similar societies may have very different burial practices, one

apparently

simple, one differentiated. Although the two societies may apparently

have

different cultural emphases expressed through their burial practices,

the

two social structures may be similar.

Such a circumstance occurs in southern Ontario with two Iroquoian

societies,

the Huron and the Neutral, during the first half of the seventeenth

century.

The two occupied contiguous areas and their cultures were broadly

similar,

despite environmental and economic differences which must have become

more

acute as the Huron gathered into Simcoe County to take advantage of

trade

with the French, while Neutral trade to the south remained important

(Jackes,

1988:109-110, 117-118,143; Jamieson, 1992:79). Although there have been

suggestions that important differences in government had appeared by

1626

(Noble, 1984, 1985 but cf. Trigger, 1985: 221-224) , the French

missionaries

laid no emphasis on any but superficial differences. In 1626 Daillon

reported

of the Huron and the Neutral that "their manners and customs are quite

the same" (LeClercq, 1881:271) and the Jesuits, writing of the period

1640-41,

also regarded the Neutral as very similar to the Huron (Charlevoix,

1900

2:152). Both societies were destroyed by Iroquois raids from the south

in 1649-50.

Sixteenth and seventeenth century Ontario is not generally

considered

to be an area of complex burial patterns because major emphasis has

been

given to the ossuary burials of the Huron. Ramsden (1990:381) has

recently

suggested that there has been "an over-emphasis on this burial mode"

and

others have drawn attention to extra-ossuary burial for individuals

other

than infants and captives (e.g. Knight and Melbye, 1983; Sutton, 1988).

Nevertheless, it must be acknowledged that ossuary burial is the

principal

mode of interment for Huron of the the sixteenth and seventeenth

centuries

and, based on the Maurice (Jerkic, 1975:48-55), Kleinburg (Jackes,

1977:8-10)

and Uxbridge (Pfeiffer, 1983) Ossuaries, we have a clear idea of this

predominant

Huron burial custom, as well as a partial record of the variations in

practice

which occurred at each site. Moreover, we have ethnohistorical

evidence,

and Huron Feasts of the Dead are known in some detail, since one such

burial

ceremony was attended by Jesuit Fathers in May 1636, at

Ossossané,

the capital of the Attignawantan Nation of the Huron. The Jesuit

description,

together with excavations of a number of comparable burial sites dating

from AD 1500 to the 1630-40s, provide us with relatively full knowledge

of the large burial pit into which the defleshed and bundled bones of

the

dead were dropped from a scaffold and subsequently stirred around (see

Kidd, 1953).

An ossuary is no more than a repository for bone, any place where

the

bones of the dead are kept. Masset (1993:102) mentions "un

'rite-ossuaire',

dont l'expression archéologique aurait été l'amas

d'ossements disloqués issu d'inhumations secondaires", and

goes

on to discuss the possibility that the "disorder" of the bones is in

the

mind of the archaeologist because of techniques of excavation or lack

of

knowledge of human osteology. European ossuary caves may, indeed, have

very careful bone placement, though without the retention of individual

identities (Zilhão, 1984). "Ossuary" has a definite meaning for

North American anthropologists, also relating to multiple secondary

burial,

but the word is not well defined. I propose that ossuary be

defined

as a multiple burial in which most individuals are interred after

natural

or artifical disarticulation. Bones may be arranged by skeletal

element,

but are rarely retained in bundles containing recognizable individuals.

In the case of sedentary or semi-sedentary populations having a

well-delimited

area in which the majority of individuals are buried, I would suggest

that

fewer than 25% of the calculated minimum number of individuals (MNI)

buried

within the cemetery area should be recognizable as individuals rather

than

simply from counts of skeletal elements.

The definition of a "recognizable individual" cannot be given in

terms

of the number of bones or articulations present: a number of major long

bones in association would probably be the best indication of a placed

bundle. Clearly associated innominates and long bones, or skull and

long

bones, or long bones and articulated vertebrae might be quite

sufficient

to constitute an individual. A number of long bones alone would be less

certainly "an individual", but attribution to a single individual might

be possible after an examination of indicators of , for example, age,

sex.,

robusticity and proportions.

The need for a definition of ossuary burial arises because the

Neutral

Nation, while broadly similar to the Huron, apparently had different

burial

practices which could justifiably be called complex because of

individuation

and differentiation. Although large multiple burial pits which have

been

called ossuaries occur among the Neutral, the Neutral did not practice

ossuary burial as defined above.

Huron ossuaries included all the dead (except infants and certain

individuals

who had died from violence, freezing or drowning) from a number of

villages

over a period which may have been up to 15 years, when a village was

moved

as soil fertility and convenient firewood decreased. Feasts of the Dead

thus occurred rarely. The ceremonies lasted some days, accompanied by

gift

giving and dancing, and culminated in the deliberate mixing of the

bones

of the dead, possibly numbering up to 700 (Patterson [1986] gives an

estimate

above this for the Kleinburg Ossuary dated around AD 1580-1600;

Katzenberg

and White [1979] give an estimate close to this for Ossossané,

dated

AD 1636). We have no evidence for similarly large burial pits among the

Neutral (Stothers, 1970).

Nearly thirty years ago, Marian White pleaded for a clearer

understanding

of the complexity of burials in southern Ontario and northern New York

state: "...ossuary must be separated from other burial types like

multiple

bundles or multiple articulated individuals placed in a single pit"

(1966:16).

She mentions that the words used by early investigators ("bone pit",

"ossuary",

etc.) in fact influence the identification of a site as Neutral or

non-Neutral.

G.K.Wright

(1963:66) implies that if a site on the Niagara Frontier has an ossuary

then it is Neutral; no ossuary, not a Neutral site. White, on the

contrary,

reassessing the Orchid Site, after stressing the inadequacy of the

data,

goes on to distinguish four types of burial, two involving ossuary

burial.

It seems that by "ossuary" White meant "disarticulated individuals" and

"thrown or placed bundles" (1966:19). However, earlier (1966:17) she

mentions

sites which have "true ossuaries because of the confusion of

thrown

bundles (my emphasis)". In order to clear up the contradiction here, a

distinction should be made between: (1) burial pits (ossuaries)

containing

the bones of many individuals in which very few articulations or placed

bundles are present; and (2) burial pits containing the bones of many

individuals

in which the majority retain articulations or the possibility of

recognizing

placed bundles which contain one or several recognizable individuals

(multiple

bundle burials).

Why bother about the distinction? I will argue that the cultural and

social meaning of the two forms of burial is distinct.

Neutral burials

When Neutral burial complexity is mentioned in the literature, it is

generally described in terms such as "ossuaries in which contents are

vertically

segregated by a clay partition or cap" (Jamieson, 1992:79). Noble

(1968)

described Neutral burials as double layered ossuaries with peripheral

burials.

This description derived partly from ten days of salvage work at the

pre-Contact

Orchid Site (White, 1966) and partly from Ridley (1961) who gathered

together

scattered information on seven Ontario Neutral sites. In only three

cases

is a false floor mentioned: in the case of the Hosken Site, by the

farmer's

son who destroyed the site (Ridley 1961:33); in the case of the Dwyer

Site

by the original excavator who mistook as exotic the drumlin clay into

which

the pit was dug (Ridley [1961:29,30] re-excavated and found no sign of

a false floor); and the Walker Site where, in 1944, amateur excavators

noted that a pit containing 11 adults and four children underlay a

larger

pit (Ridley 1961: 16,18). In 1974, further excavations at Walker showed

no evidence of false floors (M.J.Wright, 1981:119), although a subfloor

burial pit was also exposed. The 1974 sub-ossuary pit skeletons (six

adults

and six children) were described by Crerar (1983). It is likely that

multiple

and overlapping burial pits constitute the basis for the vertical

segregation

described. But it seems very possible that Neutral burial complexity

goes

far beyond a multiplicity of pits.

The Grimsby Neutral cemetery (AHGv-1) (Figure

1) provides a unique opportunity to understand Neutral burial

practices:

it was an almost undisturbed site dug in the late 1970s under difficult

salvage conditions but with efforts at archaeological precision

(W.Kenyon,

1982; Jackes, 1988). Many other Neutral sites have been

unsystematically

ravaged by "pot-hunters" since the 1820s.

Evidence for disruption of burial patterns

following epidemics

However, the possibility that Grimsby is an atypical site, the

result

of the epidemics recorded by the Jesuit fathers, must be considered

(Noble,

1985). Smallpox could have reached Neutral country by several routes in

1633-34, and a possible case of smallpox has been identified which

might

mark an even earlier epidemic (Jackes, 1983). Smallpox was certainly in

Ontario by 1639. If Noble is correct in his opinion, we cannot use

Grimsby

as an exemplar of Neutral burial practices. The Grimsby cemetery is

dated

between AD 1615 and 1650 (I.Kenyon and Fox, 1982; Fitzgerald, 1983),

and

certainly encompasses the period of famine, warfare and epidemics which

accompanied the introduction of intense trading with the French into

Ontario

and the introduction of firearms into New York State.

The 373 individuals identified in the Grimsby cemetery were

distributed

among 58 burial pits, containing from 1 to 103 individuals. The

demographic

breakdown of these burial features is diverse (Figure

2). Features 9, 26 and 1 were unusual, and these three burial

features

had more disarticulation and mixing than most others (Table

1). Feature 28 has a demographic profile similar to Feature 1 and

probably

comes from the same period. This burial was destroyed by vandals before

it could be mapped or photographed (W.Kenyon, 1982:119). Could these

atypical

features reflect the famine and disease which struck the Neutral after

1630?

In Feature 9, 47% of the individuals were between the ages of 5 and

15 (cf. 16% for the cemetery as a whole). The smallpox most prevalent

in

that age group is the least lethal type (Dixon 1962:325) and that age

group

is the least likely to succumb to the after effects of epidemic

disease.

Feature 9 shares its general pattern of age and sex distribution with

Features

11 and 45, although in a more marked form. Feature 45 was partially

disturbed,

but it seems to have had extreme disarticulation.

In the analyses of glass beads undertaken by I.Kenyon and Fox (1982)

which may allow us to add time depth to our understanding of the

Grimsby

Cemetery, Features 9 and 11 cluster together (in loose association),

quite

separately from Feature 45. None of these three falls within the same

bead

cluster as Features 1 and 28.

Feature 26 also has much disarticulation, and 40% of the individuals

were over 35 years, congruent with what we know of smallpox and measles

epidemics in previously unexposed populations (see Jackes 1986:39;

1988:138),

but it contained only shell beads and thus was not analyzed for period

by I.Kenyon and Fox. Feature 1, on the other hand, contained six shell

beads and 123 glass beads. We have no basis, therefore, for considering

all the burial features with unusual demographic characteristics or a

large

amount of disarticulation and mingling of bones to be indicative of the

late and hurried burial of victims of the final disintegration of the

Neutral

Nation. Feature 1 remains the only burial pit which is a good contender

for this title (Jackes, 1983).

Feature 1 probably does reflect the disruption at the end of the

final

period before the last Iroquois assault on the Neutral. Here there is

apparently

less disarticulation than in Features 9 and 26, but the bundles are

unusual.

Some bundles were neatly placed, suggesting individuals: however, these

could contain, for example, the bones of two left legs, but none from a

right leg. W.Kenyon (1982:10) has described the confusing picture

presented

to the excavators. Feature 1 first seemed to be an ossuary, but below

the

scatter of disarticulated bones lay a series of tightly flexed bundles,

none of which, however, contained a complete skeleton (see Jackes,

1983:76

for a description of one of the bundles). In fact, laboratory analysis

showed that bone fragments from the bundles and from the overlying

scatter

could be reconstructed into the one skeletal element.

Feature 1 has a demographic pattern that is "normal", explicable in

biological terms, and equivalent to the pattern for the cemetery as a

whole

(all features combined). This is an important reason for suggesting

that

Feature 1 may be the result of disruption. Feature 9, with its high

proportion

of juveniles all almost completely disarticulated, may on the other

hand

illustrate that disarticulation is characteristic of the burial pits in

which many juveniles were buried (Features 9, 11 and 45: see Table 1

and Table

2).

Disarticulation may thus be characteristic of one sort of Neutral

burial

feature, but extreme care in the placement of bundles containing

semi-articulated

skeletons is also quite characteristic. This is exemplified especially

by Feature 62 which is dated to the same, latest, bead period as

Feature

1.

Feature 62 contained 103 people. Source population size cannot be

calculated

accurately for a cemetery, since that requires knowledge of life

expectancy

at birth (a value which cannot be derived from most archaeological

cemeteries,

[Jackes, 1992]); but estimates of deaths per year in a stationary or

declining

population would be under 50 per year for the Grimsby source village(s)

(Jackes, 1986; 1988:128). On this estimate, both Feature 62 and Feature

9 would be comprised of: 1) the dead of several years with delayed

burial,

or 2) some of the dead of a number of villages, or 3) people who died

of

an epidemic disease. Features 62 and 9 present completely divergent

demographic

characteristics, and in each case cultural, not biological, factors

seem

to have determined interment. Thus we must exclude disease as the major

determinant of burial patterns for any Grimsby burial features other

than

Feature 1 (and Feature 28?), and consider the first two possibilities

above.

In fact, it would be impossible to distinguish these two, unless the

second

possibility encompassed only a selected group of individuals, e.g.

elderly

males.

Arrangements of bones

Feature 62 is a magnificent grave, suggestive not of the disruption

following upon an epidemic (accounts of epidemics in North America

describe

how the dead went unburied and eaten by dogs [e.g. Thwaites, 1898

16:219])

but of great attention to the bones of the dead and of delayed burial.

This is in accord with the Jesuit Relations:

Our Hurons immediately after death carry

the

bodies to the burying ground and take them away from it only for the

feast

of the Dead. Those of the Neutral Nation carry the bodies to the

burying

ground only at the latest moment possible when decomposition has

rendered

them insupportable: for this reason, the dead bodies often remain

during

the entire winter in their cabins: and, having once put them outside

upon

a scaffold that they may decay, they take away the bones as soon as is

possible, and expose them to view, arranged here and there in their

cabins

until the Feast of the Dead. These objects which they have before their

eyes, renewing continually the feeling of their losses, cause them

frequently

to cry out and to make most lugubrious lamentations, the whole in song.

But this is done only by the women (Thwaites, 1898 21:199).

This was written by Lalement on the basis of the reports of

Brébeuf

and Chaumonot who were in Neutral Country during the winter of 1640-41.

Noble (1985:140) implies that, since the description refers to the

period

after an epidemic, it cannot be taken as representative of Neutral

burial

patterns. Nevertheless, the Jesuits had come directly from Huronia,

where

an epidemic had also occurred, and were in a position to compare the

two

societies in the aftermath of epidemic illness as in the above passage.

The Jesuits saw the Huron Feast of the Dead at Ossossané in

1636,

but they saw no Neutral feast. The Neutral feast cannot have been like

that of the Huron: even in the quite large Neutral burial pits, the

numbers

of dead do not approach the numbers found in Huron ossuaries. The

fifteenth

century Glen Williams site (Neutral of the Milton Cluster) had a burial

pit of 290 individuals with partial articulations and bundles, as well

as smaller multiple and single burial features (Hartney, 1978). The

largest

known seventeenth century Neutral burial pit is one feature at Shaver

Hill,

containing a minimum of 163 people based on proximal femora (Stothers,

1971). A slightly larger oval pit at the Walker site (Ossuary C: M.J.

Wright,

1981; Crerar, 1982) may well have contained more individuals, but

nothing

approaching the 450 to 680 known to be the minimum number of skeletons

(MNI) for single sixteenth and seventeenth century ossuary pits at

Uxbridge

and Ossossané.

The burial pattern within Feature 62 at Grimsby (Figure

3) is very clear. The bones were laid more or less in an oval, "two

curved and sloping banks" (Kenyon, 1982:193) of long bones, with crania

generally placed along the central east-west passage. Stothers (1971)

describes

the main burial feature at Shaver Hill as having the skulls and long

bones

placed on one side, other adult skeletal elements on the other side,

and

most subadult postcranials in one discrete area. The oval burial

arrangement

may well find echoes in other sites: Shaver Hill, Walker and Dwyer -

the

early descriptions of the post-Contact Dwyer Site speak of the dead in

circles facing each other (Ridley, 1961:26). Within Grimsby, Feature 9

also exhibited an oval form with some vertebral columns still in

articulation,

but skeletons generally bundled, skulls to the outer part of the oval.

Feature 9/1 (a woman of mixed French/Indian ancestry; Jackes,

1988:29-32)

lay extended at the western end, her head to the north, buried with

tubes

made from the humeri of trumpeter swans.

Everyone in Feature 62, except one older male laid out at the east

end

(Fe62/58), was buried in more or less the same state of partial or

complete

disarticulation. The Neutral practice therefore seems to differ from

that

of the Huron by which very large numbers of people were buried at the

same

time. The articulated and partially articulated skeletons, present in a

Huron village just before the Feast of the Dead, must have undergone a

process of dismemberment so that they were ready for bundling in the

same

way as the disarticulated skeletons. The basis for this statement is

the

presence of numerous cut marks on Huron bones, especially at the hip

joint

and neck, indicative of purposeful dismemberment. It is particularly

telling

that there are no cut marks in the Grimsby cemetery, a point of sharp

contrast

with Huron ossuaries (Jackes, 1988:137). Furthermore, the frequent

articulation

of the spinal columns, very evident from the published Grimsby grave

plots

(W.Kenyon, 1982), contrasts markedly with Huron material from the

Kleinburg

Ossuary. Jackes (1977) examined over 12,000 vertebrae which had been

randomly

spread throughout a pit about 4 metres across: no more than a handful

of

vertebral articulations were present in the Kleinburg Ossuary. It seems

most likely that the Neutral were buried in various states of

articulation

or disarticulation (W.Kenyon 1982:230-231), without efforts made to

dismember

bodies. Huron skeletal articulations were, by contrast, purposefully

disrupted.

The Neutral may well have had quite frequent burial ceremonies,

after

the spring thaw and before the winter freeze, for example, during which

any number of people could be buried. W.Kenyon (1977:11) considered

that

a summer death lead to a single burial and that those who died in the

winter

were given spring burials in multiple graves. While this may explain

some

of the multiple burial pits, it cannot be the explanation for the

largest

of the features. Burial in the larger pits was delayed until natural

disarticulation

was almost complete, surely beyond one Ontario winter. Burial was also

delayed to some extent to allow burial by social category, very evident

from Feature 62 at Grimsby.

Grouping of individuals in Feature 62

Figure 3 shows the

distribution

of bodies in Feature 62 as determined by skulls, except for the areas

marked

x, y and z. The arrangement of skulls in a rough oval is evident, the

major

deviation being the group of subadults in the SW portion of the burial

next to the area marked x, y, z.

Individuals 103 and 104 (marked as "x") were two tall children,

buried

with mandibles, but not skulls. They were buried so close together that

their bones were mixed by the excavators. Their permanent dentitions

both

displayed an unusual eruption sequence (Jackes 1988: 21,25,132).

The area marked "y" and "z" contained the bodies of two males

(without

skulls) and one female who shared an abnormality of familial origin

(Legge-Calvé-Perthès'

Disease; see Jackes, 1988:179 index references to individuals Fe62/N,

Fe62/O,

Fe62/B).

Further evidence of familial relationships comes from the

aggregation

of minor inherited traits. At the east end of the pit lay three

individuals

with semisacralized fifth lumbar vertebrae. Seven cases of neural arch

separation of the fifth lumbar vertebra occurred, four of them in close

proximity in the southern sector of the oval. Altogether, 63% of the

fifth

lumbar vertebral neural arch anomalies in the entire site occurred

within

a 1.5m2 sector of Feature 62 (Jackes, 1988:60).

Two tall women buried together at the eastern end of Feature 62,

marked

by "c", both had inca bones (divided occipital bones in the skull;

these

two cases constitute 50% of those present in the cemetery [Jackes,

1988:12,40,132]).

Two people buried together, marked by "d", display 67% of the cases

of agenesis of the left lower third molars in the site (Jackes,

1988:40).

The evidence is very strong then, that familial relationships

pattern

the burial of individuals within Feature 62.

But sex and age clearly determine the burial pattern also. Males lie

at the eastern end of Feature 62. Only two adult males were buried at

the

west end: Fe62/4, who may have had ankylosing spondylitis (Jackes

1988:73-75),

and Fe62/2, who had a fracture of the left ulna with misaligned healing

and several ruptured intervertebral discs. The other adult males (those

without disabilities) lie in the eastern half, and at the far eastern

point

of the oval seven old males were buried together, along with one old

female

and the two tall young females with inca bones mentioned above. Since

25%

of the older males buried in the Grimsby cemetery lie within the half

metre

or so at the eastern end of Feature 62, it is justifiable to consider

that

age and sex are determinants of place of burial.

Disposition at burial of skeletons in

Feature

62

Within Feature 62, variations in the burial mode were recorded by

the

excavation team (led by K. Mills). It has been possible to correlate

burial

mode with age and sex in 67 cases (Table

3). In 57% of these individuals, the burials were described as

"accordian"

by the excavators: 69% of males vs. 54% of females (a significant

difference,

P = .002). The accordian burial mode is no doubt that described by

Kenyon

(1982:231) as "semiarticulated bundle".

The majority of the individuals were therefore buried in a state of

semi-disarticulation. Forty-two percent of individuals lay "on their

backs"

with regard to their skulls and spinal columns. Thirty-three percent

lay

"face-down", 11% on their right sides and 13% on their left sides.

There

is a difference between the sexes: males were significantly more likely

to be buried lying on their backs than females (P = .000).

Males in the accordian mode were equally likely to be prone or

supine,

whereas females were most likely to be buried face down, or on their

left

side (Table 4). Apart

from

the tendency for children 1 to 4 years of age to be buried in multiple

person bundles, and for children under 15 to be more likely to be

"jumbled",

no clear trend by age at death can be observed. At all ages, the

"accordian"

mode is most common. Adolescent and young adult males, as well as old

females,

are sometimes given "flexed" burial, implying a lesser state of

disarticulation.

In sum, although there are differences between the sexes, Feature 62

does not give us definite information on a correlation between age, sex

and the mode or posture at burial, except, perhaps in the case of

Fe62/58,

the old male buried extended across the eastern apex of the burial

oval.

There is variability in the burial postures, but the complexity to be

discerned

in Feature 62 is not based on burial mode. Rather the complexity

derives

from the clear patterning of burial placement, indicating both genetic

relationships

and status. The cemetery as a whole, in fact, supports the contention

that

age, sex and status are important determinants of place of burial.

Burial by sex and age in Grimsby Cemetery

Multiple burial features from Grimsby can be clustered in an

analysis

of the cemetery as a whole (Figure

4).

Group B are the features with many children: Features 9 and 11 (and

perhaps the disturbed Feature 45) constitute Group B features. Together

with Features 17, 18, 51, 56 and 59, these features have more females

and

children than adult males.

Group C are those features with many adult males: in Features 20,

26,

30, 36 and 62, up to 80% of individuals are adult males.

Thus, with the exception of Features 1 (and 28?), all of the

undisturbed

larger burial features in the Grimsby cemetery can be grouped into two

contrasting types of burial. This confirms the apparent tendency to

separate

males from children in burial.

In general, it is the older males who are separated from

women

and children: the old males are grouped together (Features 26, 30, 36

and

62), buried by themselves (Features 10, 60 and 61), or with older

females

(Features 23, 33 and 50). There is a tendency to group old males

together

and to separate them from the young.

Infants are generally buried separately. Young children are most

likely

of all age groups to be buried in single graves, otherwise they are

buried

with old females. The excess of 5 to 15 year olds in Feature 9 is a

clear

indication of cultural selection at burial. Late adolescents are nearly

always buried in large features and their burial pattern is different

from

that of infants and of children from 5 to 15. The separation of the

group

of features with children (Group B) and those with many males (Group C)

is underlined by the fact that all older males are buried in Group C

features

apart from one possible individual in Feature 11.

Status

If older males were of highest status in Neutral society, together

with

certain females (for example, Fe9/1 and the two women buried at the

eastern

end of Feature 62), it is clear that burial in the Grimsby Cemetery did

differentiate between higher and lower status individuals. However, Fox

considers that the Grimsby Cemetery is unique -- apart perhaps from the

extensively disturbed and incompletely excavated Walker Site --

possibly

a spiritual centre with burials of high status individuals (I.Kenyon

and

Fox, 1982:13; Fox, in litt. 21/1/83). It is completely

justifiable

to question whether the demographic profile presented by the Grimsby

skeletons

has biological meaning, or whether the aggregation of skeletons in the

cemetery has cultural, rather than biological meaning . In so far as it

is possible for osteological evidence to stand alone, without its

archaeological

context, the Grimsby skeletons suggest that, although burial is by

cultural

category, the total sample indicates a biological population.

The evidence which comes from an analysis of the age at death

distribution

suggests that the Grimsby Cemetery as a whole could represent a single

community (a town or an intermarrying group of villages). The sample

gives

no indication of bias such as would be expected were high-status

individuals

assumed to be older males and females. In total, the Grimsby sample

gives

strong evidence of high mortality virtually unparalleled in the

demographic

literature, on a par with that in the Arikara post-Contact sites

(Jackes,

1986), because more subadults aged 5 to 20 are buried than would be

expected

except under very severe mortality conditions.

It is extremely difficult, perhaps impossible, to provide accurate

ages

at death. For this reason, we must look for other evidence to sustain

the

hypothesis that Grimsby people died at an earlier age than those in

other

Ontario burial sites. In fact, the suggestion of a low mean age at

death

is strongly supported by examination of dental pathology. Dental

pathology

is an age-dependent characteristic, so that early age at death would

lower

rates of dental pathology very strongly. Grimsby has reduced dental

pathology,

relative to other Ontario populations, although stable isotope and

trace

element analyses do not suggest that the diet was less cariogenic

because

of reduced dependence on maize (Jackes, 1988:118,125). The hypothesis

of

high mortality is thus supported by independent evidence from dental

pathology.

Burial by family relationship at Grimsby

It has long been considered that family relationships may determine

placement within the smaller burial units in Neutral cemeteries.

Crerar's

finding (1983) of a woman and child with bipartite patellae buried

together

at Walker, the burial together of two slightly anomalous individuals in

Feature 17 at Grimsby (Jackes, 1988:13), as well as the overwhelmingly

strong evidence provided by Feature 62, all point to the burial

together

of closely related individuals.

Burial by physical condition

The extent to which individuality is maintained in the Grimsby

cemetery

is noteworthy. People are more or less people. There are a few cases

where

people were, it seems on purpose, buried without their heads. These

have

been discussed above in the context of a detailed description of

Feature

62: the adults were people with marked disabilities. No skull was

associated

with Feature 1/33, an individual who may have suffered from smallpox

osteomyelitis

(Jackes, 1983), but Feature 1 cannot be regarded as typical of Grimsby

burials.

Given the recorded emphasis on resurrection noted for the Neutral

(G.K.Wright,

1963:19-20), one might suspect that individuality was retained for a

purpose:

The Attiuoindarons enact Resurrections of

the

dead, chiefly of those who have deserved well of their country by

remarkable

services, to the end that the memory of illustrious and valorous men

may

in some manner come to life again in the person of others. So they call

meetings with that object, and hold councils, at which they choose some

one among them who possesses the same virtues and characteristics, if

that

is possible, as he whom they wish to resuscitate, or at least one whose

manner of life is irreproachable among savages. When ready to proceed

to

the Resurrection, they all rise except the one to be resuscitated, on

whom

they bestow the name of the dead man, and all putting their hands far

down

pretend to lift him from the ground, meaning thereby that they draw out

of the tomb that great man who was dead and restore him to life in the

person of the other, who rises to his feet, and after great applause by

the people receives the presents offered him by those taking part. They

also congratulate him with several feasts and henceforth treat him as

the

dead man whom he represents, and thus the memory of worthy people and

excellent

brave chiefs never dies among them.

Nevertheless, even in this aspect of society, we cannot find a clear

distinction

between the Neutral and the Huron. Tooker (1967:44-45) has provided a

summary

discussion on the identification of important Huron chiefs with their

Nation

and on the ceremonies by which a Huron chief might be "resuscitated"

through

the granting of the name of the deceased to his successor (see

Hickerson,

1960 for the equivalent ceremony among Algonkians who borrowed it from

the Huron).

While we find no clear distinction in the ethnohistorical accounts

of

the two societies, there is every reason to consider that the Neutral

ceremonial

treatment of the dead was not of the Huron type. The emphasis was on

community

among the Huron (Tooker 1967:139-140), and the Huron Feast of the Dead

was the occasion for stressing corporate relations: the dead were

brought

and their bones mingled. The life of the dead was thought of as a

reflection

of the world of the living (Tooker 1967:139-149). Their living

relatives

feasted together and indulged in gift exchanges in a classical

anthropological

rite of community intensification. (see also Hickerson, 1960, 1963).

In contrast, the Neutral burials seem to emphasise distinctions

among

the dead. The reasons for this may lie in differentiation in the fate

of

the dead in the afterlife. We know from the Jesuit accounts of the

Huron

that the souls of children, the elderly, perhaps the disabled, those

who

died in battle, suicides (Tooker, 1967:140-141; Ramsden, 1990:380)

might

not end up in the general village of the dead.

While the Neutral may have laid greater emphasis on these

distinctions

than the Huron, it is more likely that the explanation for the

difference

lies in the nature and function of Neutral burial areas. It seems very

likely that the cemetery area associated with a Neutral population

centre

was used more often and over a longer period of time than was the case

for Huron ossuaries. A single Huron burial pit contains the bodies of

those

who died during the period of the occupation of one village site, all

of

whom were buried in one long and ornate ceremony. The Grimsby cemetery

probably had an extended period of use and was the scene of numerous

burial

ceremonies (see Jackes, 1986:40-41).

Bead clusters and demography

Kenyon and Fox (1982) suggest that the Grimsby Cemetery may cover as

much as 35 years and they distinguish three phases based on glass beads

included in 29 features, each phase covering 10 years or more. Fox has

kindly provided his assesment of the temporal sequence of all possible

Grimsby features, although "these temporal identifications stretch

intuitive

assessment to the limits, as they are often based on limited artifact

samples"

(in litt. 21/1/83).

The first phase (II) is represented by only six features and 27

individuals,

too few to make any determination of demographic trends. Feature 45 is

included in this phase. The second phase (IIIA) comprises 114

individuals

in nine features, including Features 9, 11 and 36. The third phase

(IIIB)

includes Features 1, 28 and 62, and has in it 146 individuals in 15

features.

The groupings deduced from bead types and from the sex and age

make-up

of the features cross-cut each other; but Jackes (1986:45) has shown

that

the sex and age breakdown for the two later bead phases (IIIA and IIIB)

are significantly different. The earlier bead phase has significantly

more

children, while the later phase has significantly more males and

significantly

more older people of both sexes.

It is therefore essential that we consider the possibility that the

feature groups B and C and the bead phases reflect, not cultural

selection

at burial, but changes in demography over time.

Demographic analysis undertaken here is of the limited type designed

to assess bias or trends in populations undergoing increase or decline

(Jackes, 1986;1992). Analysis of the last bead period (Phase IIIB)

provides

a scenario of fairly high mortality in a population which is not in

active

decline (mean childhood mortality [MCM] = .126, juvenile:adult ratio

[J:A]

= .310). Analysis of the penultimate bead phase (Phase IIIA), however,

provides a picture of extreme bias (MCM = .219, J:A = .766), or else

population

increase (MCM = .19, J:A = .59 at r = +.01) beyond the levels

imaginable

within the context of fertility in Ontario in the seventeenth century

(Jackes,

1994). Given this, we must consider the possibility that feature

groupings

and bead phases are broadly contemporaneous aspects of the same burial

mode in which adult males and young children are most likely to be

given

separate burial (see Jackes, 1988:141).

Such an interpretation is in line with the hypothesis of Fitzgerald

(1983:18): "It would seem rather than being a distinct bead period ...

Period 3a is an assemblage that would seem to span the latter years of

Period 2 and the early part of ... Period 3b."

Conclusions

While Figure 5

illustrates how disparate the features are in their demographic makeup,

it cannot encompass the extreme complexity of single and multiple

graves

and old and young adults, infants, children and adolescents.

Explanations

in terms of high status burials, or in terms of smallpox epidemics,

while

not irrelevant, cannot embrace all the complexity of Grimsby Cemetery.

The cemetery as a whole appears to represent a community, most probably

a community which was suffering an extreme rate of mortality. Mortality

among subadults was excessively high, and the community could not have

sustained itself for long (in this context, it is relevant to note that

the Grimsby skeletons do not provide us with any evidence of an influx

of refugees from Huronia, or from other Neutral villages: distance

studies

of traits of the teeth, crania and post-cranials indicate that the

Neutral

at Grimsby constituted a gene pool, separable from those represented by

other Neutral skeletal collections [Jackes, 1988]).

It is unfortunate that we have little to compare Grimsby with,

although

Grimsby is not an isolated example. Shaver Hill (AD 1600-1620) seems to

have had careful bone arrangements and burial by age categories

(Stothers,

1971, 1972), but the information is sketchy. White (1966:6) mentions

arranged

bones in the pre-Contact Orchid Site, but admits that, under the

conditions

of excavation, it was impossible to confirm the observation that the

burial

pit was outlined by skulls and that skulls and pelves were often

associated.

The Walker Site had a cemetery like that of Grimsby, and is at least

partly

contemporaneous. Descriptions of other Neutral burial sites provide

little

firm information: some sites have been "potted" continuously since the

last century, some sites have now disappeared and all that is left are

vague references to "ossuaries".

The evidence points to Grimsby being neither unique nor the result

of

epidemics, but the common pattern for Neutral cemeteries in the

seventeenth

century. That being the case, Neutral burial is nothing like that of

the

Huron who intermingled the dead in stressing wider corporate

relationship

and perhaps trading relationships. The Neutral were concerned to

emphasize

relationships within the smaller corporate units important to them,

with

much stress upon the categorization of individuals by age and by sex

and

ultimately by social status.

Ossuary burial seems not to have been consonant with Neutral

beliefs,

and we have no evidence that the Neutral practised ossuary burial as

defined.

Rather the Neutral sites, in general, probably had a mixture of single

and multiple burials, the latter varying in size and often having

arrangements

of placed bundles. These bundles of semi-articulated or disarticulated

individuals were placed with attention to age, sex, status and family

relationships.

Burials of the various types may overlie and disturb each other.

It is not possible here to explain the differences between Huron and

Neutral burial practices, apart from suggesting that Neutral villages

were

occupied for longer periods than those of the Huron, since there is no

good ethnohistorical evidence of marked differences in social

structures.

Therefore, it is not always warranted to make an interpretative leap

and

conclude that complexity in burial practices based on differentiation

and

individuation reflects greater complexity in social structure .

Acknowledgments

Working with Walter Kenyon was an experience I would not have wanted

to miss. I wish that circumstances had been different and that I could

have continued our discussions on the details of Grimsby once the

osteological

analyses were complete. I am grateful to Bill Fox for information on

his

work on bead phases at Grimsby and to Milt Wright for discussions on

Neutral

archaeology.

References

-

Dixon, C.W. (1962). Smallpox. London: Churchill.

-

Charlevoix, P.F.X. (1900). History and General Description of New

France

translated and published by J.G. Shea. N.Y.

-

Crerar, J.M. (1982). The historic Neutral burial grounds at the Walker

Site. MS on file with Dr. S. Saunders, Department of Anthropology,

McMaster

University, Hamilton.

-

Crerar, J.M. (1983). An unusual sub-ossuary pit in the Walker Site

burial

grounds. Paper presented to the Canadian Archeological Association.

Halifax,

Nova Scotia. April, 1983.

-

Fitzgerald, W.R. (1983). Further comments on the Neutral glass bead

sequence.

Arch

Notes 83-1:17-25.

-

Gualtieri, M. and M. Jackes (1993). The cemetery areas: material

culture

and social organization. Pp. 140-226 in M. Gualtieri (ed.) Fourth

Century

B.C. Magna Graecia: a case study. Paul Åströms

förlag,

Partille, Sweden.

-

Hartney, P.C. (1978). Palaeopathology of Archaeological Aboriginal

Populations

from Southern Ontario and Adjacent Region. Ph.D. Thesis, Department

of Anthropology, University of Toronto.

-

Hickerson, H. (1960). The feast of the dead among the seventeenth

century

Algonkians of the Upper Great Lakes. American Anthropologist 62(1):

81-107.

-

Hickerson, H. (1963). The sociohistorical significance of two Chippewa

ceremonials. American Anthropologist 65(1): 67-85.

-

Jackes, M.K. (1977). The Huron Spine. Ph.D. Thesis, Department

of

Anthropology, University of Toronto .

-

Jackes, M.K. (1982). Historic Neutral Burial Practices. Paper presented

to the 10th Annual Meeting of the Canadian Association for Physical

Anthropology,

Guelph, November, 1982.

-

Jackes, M.K. (1983). Osteological evidence for smallpox: a possible

case

from seventeenth century Ontario. American Journal of Physical

Anthropology

60:75-81.

-

Jackes, M.K. (1986). Mortality of Ontario Archaeological Populations.

Canadian

Journal of Anthropology 5:33-48.

-

Jackes, M.K. (1988). The Osteology of the Grimsby Site.

Edmonton:

Department of Anthropology, University of Alberta.

-

Jackes, M.K. (1992). Paleodemography: Problems and Techniques. In S.R.

Saunders and M.A. Katzenberg (eds.) Skeletal Biology of Past

Peoples:

Research Methods. New York: Wiley-Liss, pp. 189-224.

-

Jackes, M.K. (1994). Birth Rates and Bones. In A. Herring and L. Chan

(eds.)

Strength

in Diversity: A Reader in Physical Anthropology. Canadian Scholars'

Press Inc.

-

Jamieson, S.M. (1992). Regional interaction and Ontario Iroquois

evolution.

Canadian

Journal of Archaeology 16:70-88.

-

Jerkic, S. (1975). An Analysis of Huron Skeletal Biology and

Mortuary

Practices: The Maurice Ossuary. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of

Anthropology,

University of Toronto .

-

Katzenberg, M.A. and R. White (1979). A paleodemographic analysis of

the

os coxae from Ossossané ossuary. Canadian Review of Physical

Anthropology 1:10-28.

-

Kenyon, I. and W. Fox (1982). The Grimsby Cemetery - a second look.

KEWA

(Newsletter of the London Chapter, Ontario Archaeology Society)

82-9:

3-16.

-

Kenyon, W.A. (1977). Some bones of contention. Rotunda 10:4-13.

-

Kenyon, W.A. (1982). The Grimsby Site, an Historic Neutral Cemetery.

Toronto: Royal Ontario Museum.

-

Kidd, K.E. (1953). The excavation and historical identification of a

Huron

ossuary. American Antiquity 18:359-379.

-

Knight, D. and J. Melbye (1983). Burial patterns at the Ball Site. Ontario

Archaeology 40:37-48.

-

LeClercq, C. (1881). First Establishment of the Faith in New France.

Translated and published by J.G. Shea. N.Y.

-

Masset, C. (1993). Les Dolmens: Sociétés

néolithiques

et pratiques funéraires. Editions Errance, Paris.

-

Noble, W.C. (1968). Iroquois archaeology and the development of

Iroquois

social organization (1000-1650 A.D.). Ph.D. dissertation,

Department

of Archaeology, University of Calgary.

-

Noble, W.C. (1984). Historic Neutral Iroquois settlement patterns. Canadian

Journal of Archaeology 8:3-37.

-

Noble, W.C. (1985). Tsouharissen's chiefdom: an early historic 17th

century

Neutral Iroquoian ranked society. Canadian Journal of Archaeology

9:133-146.

-

Patterson, D.K. (1986). Changes in oral health among prehistoric

Ontario

populations. Canadian Journal of Anthropology 5:3-13.

-

Pfeiffer, S. (1983). Demographic parameters of the Uxbridge ossuary

population.

Ontario

Archaeology 40: 9-14.

-

Ramsden, P.G. (1990). The Hurons: archaeology and culture history. Pp.

361-384 in C.J. Ellis and N. Ferris The Archaeology of Southern

Ontario

to A.D. 1650. Occasional Publications of the London Chapter,

Ontario

Archaeological Society Inc., Publication Number 5. London, Ontario.

-

Ridley, F. (1961). Archaeology of the Neutral Indians. Port

Credit,

Ontario: Etobicoke Historical Society.

-

Rothschild, N.A. (1979). Mortuary behavior and social organization at

Indian

Knoll and Dickson Mounds. American Antiquity 44:658-675.

-

Stothers, D.M. (1970). A comparative analysis of Huron and Neutral

ossuary

burial information. Toledo: The Toledo Area Aboriginal Research

Society.

-

Stothers, D.M. (1971). The Shaver Hill burial complex: reflections

of

a Neutral Indian Population. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation,

Department

of Anthropology, Case Western Reserve University.

-

Stothers, D.M. (1972). The Shaver Hill burial complex - reflections of

a Neutral Indian population: a preliminary statement. Toledo Area

Aboriginal

Research Bulletin 2(1): 28-37.

-

Sutton, R.E. (1988). Palaeodemography and late Iroquoian ossuary

samples.

Ontario

Archaeology 48:42-50.

-

Thwaites, R. (1898). The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents.

73 Vols. Cleveland: Burrows.

-

Tooker, E. (1967). An Ethnography of the Huron Indians 1615-1649.

Huronia Historical Development Council, Sainte-Marie among the Hurons,

Midland, Ontario.

-

Trigger, B.G. (1985). Natives and Newcomers: Canada's "Heroic Age"

Reconsidered.

Kingston and Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press.

-

White, M.E. (1966). The Orchid Site ossuary, Fort Erie, Ontario. Bulletin

of the New York State Archaeological Association 38: 1-24.

-

Wright, G.K. (1963). The Neutral Indians, a source book. New

York

State Archaeological Association, Occasional Paper No. 4.

-

Wright, M.J. (1981). The Walker Site. Archaeological Survey of

Canada

Paper No. 103. National Museum of Man Mercury Series. Ottawa.

-

Zilhão, J. (1984). A Gruta da Feteira (Lourinhã):

Escavação

de salvamento de uma necrópole neolítica. Trabalhos

de

Arqueologia 1. Lisbon: Instituto Português do Património

Cultural.

Table 1: Number of individuals with

full

or partial articulations in representative burial features at Grimsby

(undisturbed single burials were articulated).

back to text

|

Feature

|

Number buried

|

Number of individuals with articulations reported by

excavators

|

N. partial spines plotted

|

% with articulations

|

% with partial spine articulations included

|

|

1

|

17

|

0

|

2

|

0

|

12

|

|

2

|

1

|

primary burial

|

|

100

|

|

|

5

|

4

|

1

|

|

25

|

|

|

6

|

2

|

disturbed

|

|

|

|

|

7

|

3

|

disturbed

|

|

|

|

|

9

|

58

|

1 (Fe9/1)

|

16

|

1.7

|

28

|

|

11

|

25

|

2+? (vandalized)

|

|

8

|

|

|

12

|

1

|

primary burial

|

|

100

|

|

|

14

|

2

|

1

|

|

50

|

|

|

17

|

6

|

1

|

3

|

17

|

50

|

|

19

|

4

|

4

|

|

100

|

|

|

20

|

3

|

2

|

|

66.7

|

|

|

26

|

15

|

2

|

|

13.3

|

|

|

28

|

10

|

vandalized

|

|

|

|

|

30

|

6

|

6

|

|

100

|

|

|

31

|

1

|

1? disturbed

|

|

|

|

|

33

|

2

|

2

|

|

100

|

|

|

36

|

20

|

2

|

5

|

10

|

25

|

|

38

|

1

|

1

|

|

100

|

|

|

39

|

2

|

2

|

|

100

|

|

|

45

|

18

|

1

|

|

5.6

|

|

|

51

|

5

|

vandalized

|

|

|

|

|

53

|

1

|

1? disturbed

|

|

|

|

|

55

|

2

|

1

|

|

50

|

|

|

56

|

4

|

2

|

|

50

|

|

|

58

|

3

|

poor preservation

|

|

|

|

|

59

|

4

|

1

|

2

|

25

|

50

|

|

60

|

1

|

1? disturbed

|

|

|

|

|

62

|

103

|

10

|

28-30

|

10

|

27-30

|

|

63

|

1

|

1

|

|

100

|

|

Table 2: Age, sex and numbers in burial

features

back to text

|

Number of Individuals

|

Burial pits

|

Age 0-5

|

Age 5-15

|

Age 15-20

|

Males

20+

|

Females

20+

|

Adults of

unknown sex

N

|

|

N

|

N

|

%

|

N

|

%

|

N

|

%

|

N

|

%

|

N

|

%

|

|

1

|

26

|

8

|

17

|

5

|

7

|

0

|

0

|

8

|

7

|

5

|

5

|

0

|

|

2

|

9

|

5

|

11

|

3

|

4

|

0

|

0

|

2

|

2

|

6

|

6

|

2

|

|

3-9

|

15

|

8

|

17

|

12

|

16

|

6

|

16

|

17

|

16

|

20

|

20

|

0

|

|

10-19

|

4

|

7

|

15

|

9

|

12

|

5

|

13

|

22

|

20

|

16

|

16

|

1

|

|

20-29

|

2

|

4

|

8

|

7

|

9

|

9

|

24

|

12

|

11

|

11

|

11

|

2

|

|

58

|

1

|

8

|

17

|

27

|

36

|

7

|

18

|

2

|

2

|

14

|

14

|

0

|

|

103

|

1

|

7

|

15

|

12

|

16

|

11

|

29

|

45

|

42

|

28

|

28

|

0

|

|

Total

|

58

|

47

|

100

|

75

|

100

|

38

|

100

|

108

|

100

|

100

|

100

|

5

|

Table 3: Modes of burial in Feature 62

back to text

|

Mode

|

Males

|

Females

|

Juveniles

|

|

Accordian

|

20

|

14

|

4

|

|

Flexed

|

3

|

4

|

1

|

|

Extended

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

|

Jumbled

|

0

|

3

|

2

|

|

Bundle

|

3

|

3

|

0

|

|

Multiple bundle

|

2

|

2

|

5

|

|

TOTALS

|

29

|

26

|

12

|

Table 4: Feature 62 Burial Disposition

back to text

| Disposition |

Males

|

Females

|

Juveniles

|

|

on back

|

12

|

5

|

2

|

|

face down

|

8

|

7

|

0

|

|

on right side

|

3

|

2

|

0

|

|

on left side

|

2

|

4

|

0

|

|

TOTALS

|

25

|

18

|

2

|

|

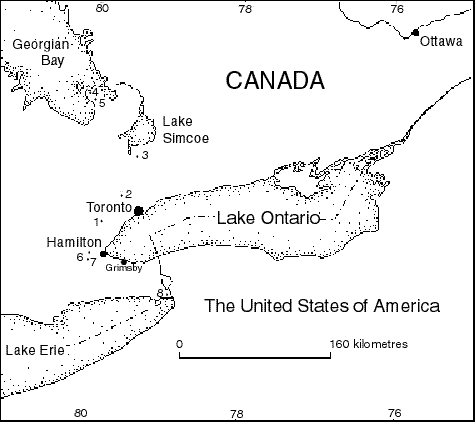

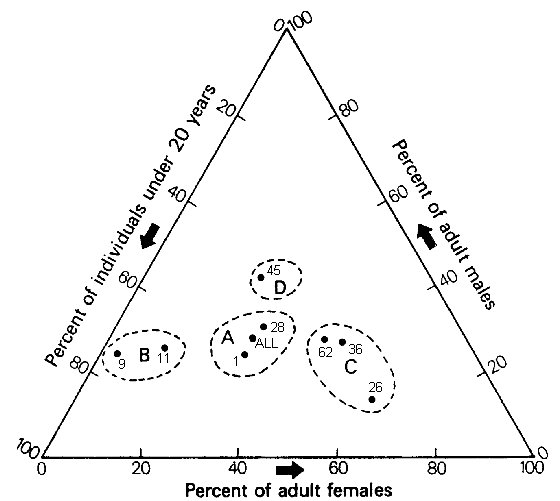

Figure 1.

Major sites mentioned in the text:

1- Glen Williams;

2 - Kleinburg;

3 - Uxbridge;

4 - Maurice;

5 - Ossossané;

6 - Shaver Hill;

7 - Walker;

8 - Orchid).

back to text

|

|

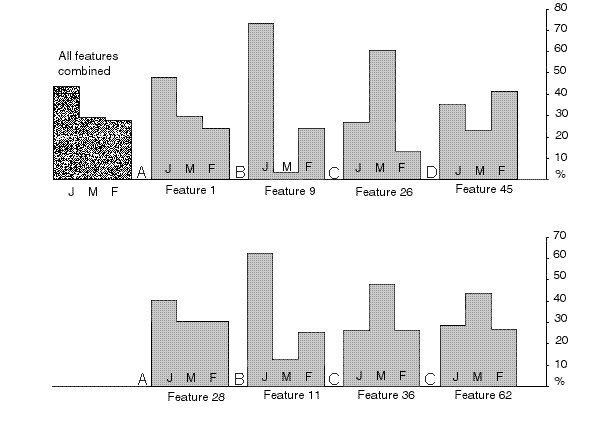

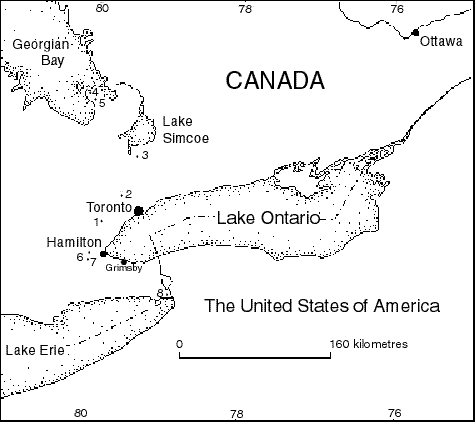

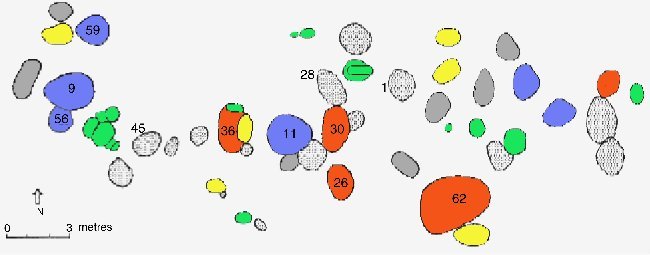

Figure 2.

Percentage of dead by age

(J - juveniles)

and sex

(M, F - males and females over 20 years of age)

for some features in the Grimsby Cemetery.

back to text

|

dark screen adult males; light screen adult

females;

stipple

under 20 years of age

|

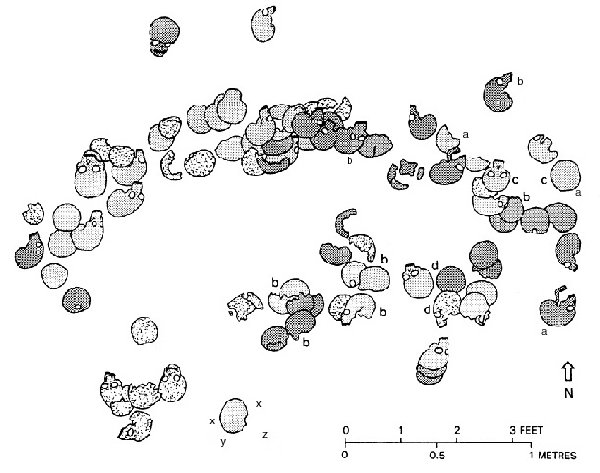

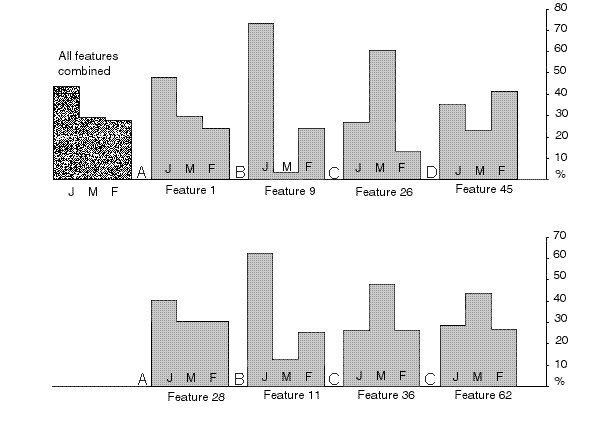

Figure 3.

Distribution of skulls in Feature 62 at Grimsby.

back to first mention in text

Key: a. semisacralized L.5;

b. L.5 neural arch separated;

c. Inca bone;

d. M3 agenesis;

x. area of burial of Fe62/103 and Fe62/104;

y. area of burial of Fe62/N and Fe62/O;

z. area of burial of Fe62/B.

back to detailed discussion

|

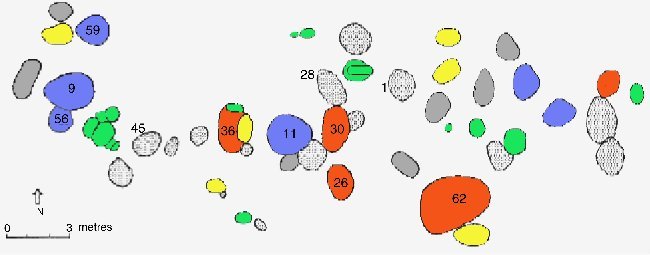

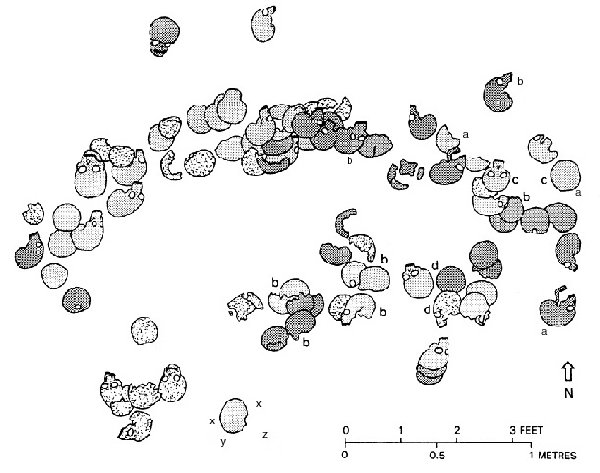

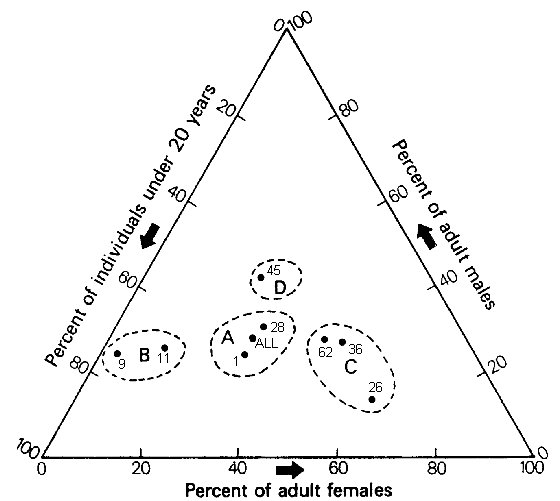

Key: red - Group C, many adult males; blue

- Group B, many females and juveniles;

yellow - adult female, single burial; grey - adult

male,

single burial; green - infants or children only;

hatched - vandalized or indeterminate multiple burials.

|

Figure 4.

Distribution of features within the Grimsby Cemetery.

back to text

|

|

Figure 5.

Composition of larger burial features by age and sex.

back to text

|